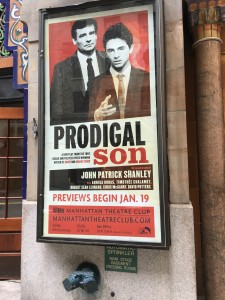

There comes a moment in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, when Stephen Dedalus, the author’s alter ego states, “Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” The novel chronicles how a young man creates himself both as an individual and as an artist. As he authors himself, he walks through the fires large — nationalism, religion — and small — the struggles of adolescence, a dysfunctional family. Last month when I saw Prodigal Son, I came to the conclusion as the lights came up for the curtain call that, at last in John Patrick Shanley, we had our American Joyce.

Much can and has been said about Prodigal Son, but I want to here focus on that Joyce connection. Shanley, as with Joyce, has brought his adolescent self to life through words — through poetry and prose, through philosophy and theology — to be reconsidered, reexamined, to undergo catharsis as much for the audience as no doubt himself. His avatar, Jim, is truly a remarkable creation. And I should add that in Timothée Chalamet (famous for Homeland and Interstellar) Shanley has found the ideal collaborator. Actor and author do not shy away from Jim’s darkness — he says and does the stupid things teenagers often do as they wrestle with the twin tensions of childhood and adulthood — his brilliant narcissism, or his self-destructive impulses. He is not likable the way teenagers on television sit-coms are often likable. But he is engaging and endearing. His darkness is understandable, his pain a source of empathy, his yearning to connect with an world of ideas that he cannot yet quite touch remarkable. The play is no better than when Shanley lets Chalamet tear into a monologue, trip the light fantastic in a way that has the raw magic of stream-of-consciousness to find truths (human truths, perhaps, if not universal truths) in the most Joycean, or given the play’s setting in the 1960’s, Kerouacian way. The actor opens up to show us both the wonder and pain within.

Stanley is at his most powerful when his flawed characters wrestle with faith and doubt (in reference to his perhaps most famous work). What intrigues here for Jim is the same that intrigues for Stephen: the temptation for sin he finds within and not from without. He recognizes the darkness in himself — the darkness that dwells within all of us — but he is intelligent enough (brave enough? foolish enough?) to address it and not ignore it as most do. What will win inside him? Will what Lincoln called “the better angels of our nature” eventually hold sway? Jim does not know. He wants to find the answer, though perhaps it too scares him.

Louise, the headmaster’s wife, tells him, “I think James Quinn is a fine outline, and it’s up to you to fill it in.” Shanley, I think bravely, undertakes the return to his tumultuous past (for the nation, for himself) to try and unlock the puzzle of his earlier life. Kudos to him for not giving us pat answers — for still not truly knowing what the answers are yet, though he surely has a better grasp of the questions.

Shanley, for me, became the American Joyce the day he decided to put Prodigal Son on stage. Here is the kicker. I do not believe he set out to do that. If he had, his work would have been derivative, pretentious, blah. He just sat out to write the most searingly honest play he could. In so doing, he stumbled onto something unintended and rare: a work uniquely specific and uniquely universal. Joyce writes of Stephen, “He did not want to play. He wanted to meet in the real world the unsubstantial image which his soul so constantly beheld. He did not know where to seek it or how, but a premonition which led him on told him that this image would, without any overt act of his, encounter him.” Shapely could write the same of Jim.